On paper, a 4.3% GDP growth rate should signal a booming economy. Governments tout it. Markets celebrate it. Headlines frame it as proof of recovery or resilience. Yet for millions of households, daily life feels anything but prosperous.

This disconnect — strong headline growth paired with widespread economic anxiety — is what economists increasingly call the GDP paradox. To understand it, we need to look beyond aggregate numbers and examine how growth is actually experienced on the ground.

What GDP Really Measures — and What It Doesn’t

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) measures the total value of goods and services produced within a country. It’s a useful macroeconomic indicator — but it was never designed to capture well-being, financial security, or quality of life.

As the World Bank has repeatedly noted, GDP says nothing about:

- Income distribution

- Cost of living pressures

- Household debt burdens

- Job quality or stability

In other words, an economy can grow rapidly while large segments of the population fall further behind.

Where the 4.3% Growth Is Actually Coming From

Recent growth spurts are often driven by a narrow set of factors:

- Corporate profit expansion

- Government spending and stimulus

- Capital-intensive sectors like energy, defense, or technology

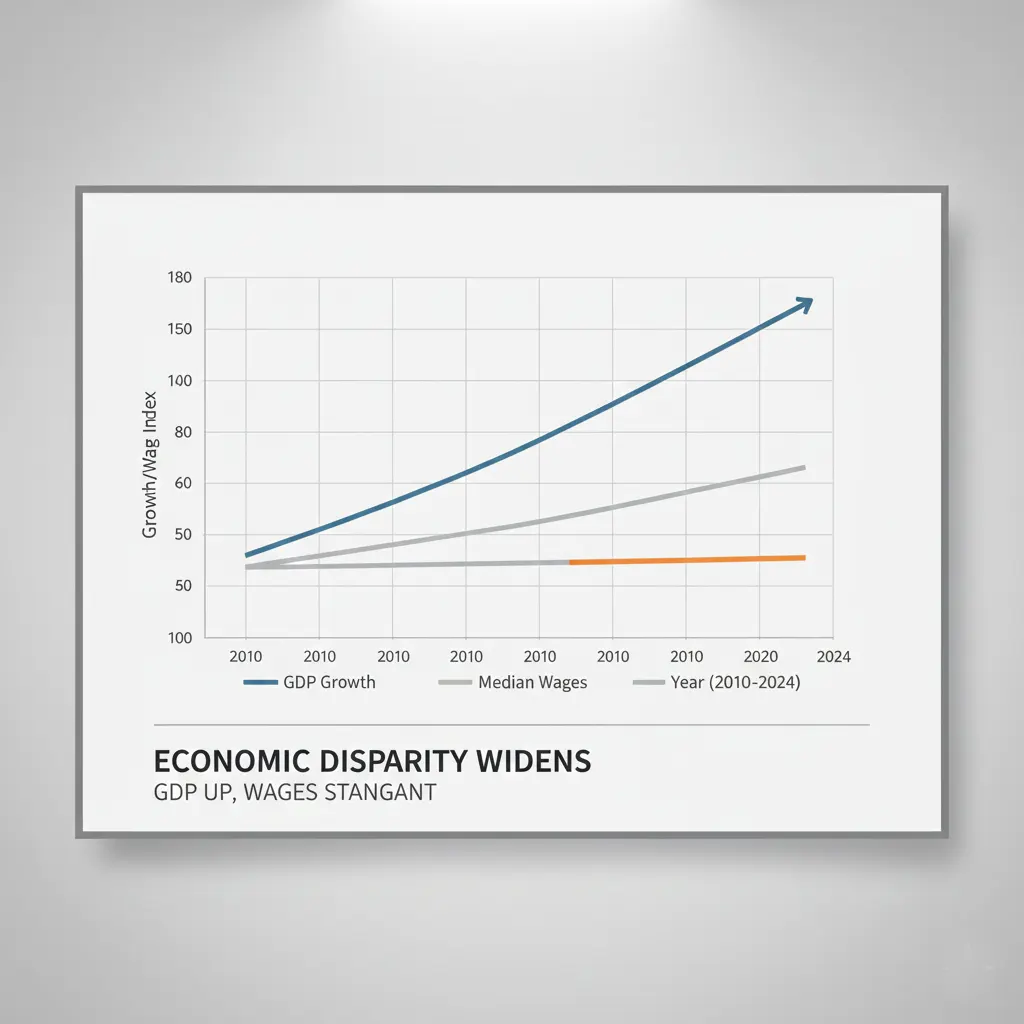

These areas boost national output but don’t necessarily translate into higher disposable income for average workers. According to analysis from OECD, productivity gains and profits have increasingly decoupled from wage growth over the past two decades.

Inflation: The Silent Erosion of “Growth”

Even when wages rise nominally, inflation can erase those gains. Essentials like housing, food, healthcare, and insurance have outpaced overall inflation in many advanced economies.

Data tracked by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics shows that shelter and food costs consume a growing share of household budgets — leaving families feeling poorer even as GDP climbs.

The result is a psychological contradiction: the economy is “growing,” but purchasing power is shrinking.

Asset Inflation vs. Everyday Reality

A significant portion of modern GDP growth is tied to asset appreciation — stocks, real estate, and financial instruments. These gains disproportionately benefit higher-income households who already own assets.

For renters, first-time homebuyers, or younger workers without investment portfolios, asset-driven growth feels exclusionary rather than uplifting.

Why Job Numbers Can Be Misleading

Employment figures often accompany GDP headlines, but job quantity doesn’t equal job quality. Many new roles are:

- Low-wage or part-time

- Lacking benefits or long-term security

- Vulnerable to automation or outsourcing

Research from Brookings Institution suggests that labor market precarity is one of the strongest predictors of economic dissatisfaction — regardless of GDP performance.

The Distribution Problem

The central flaw of GDP is that it aggregates gains without regard to who receives them. A small increase in income for millions of people can matter more socially than massive gains concentrated at the top — but GDP treats both scenarios equally.

As inequality widens, growth feels abstract, distant, and politically hollow.

Beyond GDP: Rethinking Prosperity

Economists and policymakers are increasingly exploring alternative metrics such as:

- Median real wage growth

- Household net worth by income group

- Cost-of-living–adjusted income

- Well-being and health indicators

Institutions like the United Nations argue that sustainable prosperity requires shifting focus from raw output to lived economic experience.

A 4.3% GDP growth rate may impress economists and investors, but prosperity isn’t felt in spreadsheets — it’s felt at grocery stores, rent payments, and medical bills.

Until growth translates into affordable living, rising real wages, and economic security, the GDP paradox will persist — and public skepticism toward “good economic news” will only deepen.

#GDP #EconomicGrowth #CostOfLiving #Inflation #EconomicReality #Inequality #GlobalEconomy #FinanceExplained